Let’s face it: life is sometimes quite hard. It doesn’t matter who you are; all of us inevitably bump into challenges and hardships that are beyond our control. If you’re on this planet long enough, you’re going to be hit with some form of misattunement or loss or abuse or divorce or disease or a car accident or an environmental disaster or war or who knows what. Sometimes these events are so overwhelming that we don’t even have the capacity to react or respond to them. You can’t stop these things from happening; they’re just part of what it means to be human. And to make matters even trickier, epigenetic studies now suggest that—in a manner of speaking—we may inherit the struggles of our ancestors. In one way or another, we’re affected by everything that our grandparents, great-grandparents, and so on went through and suffered from. But we’re also the products of their resiliency. Throughout time and our evolution as a species, people have been experiencing hardships and doing their best to endure and survive them.

So, life is hard, and it isn’t your fault. That’s just the way it is, which means that you can stop blaming yourself as if you alone are responsible. There are countless ways for any of us to end up experiencing trauma, and most of them have nothing to do with how we live our life or what kind of person we are. That’s the bad news.

But there’s good news, too.

We can do something about it.

We’re all born with an amazing capacity to survive, heal, and thrive, which is precisely the reason we’ve made it this far to begin with. It’s what we’re built for.

Before we go on, I want to be clear about what I mean when I say the word trauma. Without getting too technical, trauma is what results from experiencing an event over which you have little control; sometimes—as in the case with major accidents—you don’t even have time to brace yourself for the impact. These events overwhelm your ability to function normally, and this can make you lose trust in your feelings, thoughts, and even your body. In this way, trauma is a form of tremendous fear, loss of control, and profound helplessness.

I’ve also started thinking of trauma in terms of connection. The theme of broken connection has come up in my work repeatedly over the years: broken connection to our body; broken connection to our sense of self; broken connection to others, especially those we love; broken connection to feeling centered or grounded on the planet; broken connection to God, Source, Life Force, well-being, or however we might describe or relate to our inherent sense of spirituality, open-hearted awareness, and beingness. This theme has been so prominent in my work that broken connection and trauma have become almost synonymous to me.

When trauma hits us or we’ve experienced a lot of relational wounding, we can feel like we’re utterly disconnected—like we’re a tiny little me who’s isolated and all alone, as if we’re in our own little bubble floating around in a sea of distress, cut off from everyone and everything. I think it’s our work to pop that imaginary bubble, or at least to build bridges that connect us to others we care about. Unresolved trauma, in my opinion, has led to a nationwide epidemic of loneliness and hurt. And it isn’t just in our country. The evidence of this type of pain worldwide is readily available any time you turn on the news. That’s not the whole story, fortunately. We can heal and change. All of us are capable of healing and repairing these severed connections: to ourself, other people, the planet, and whatever it is that holds it all together.

But we can’t do it alone.

First of all, we not capable of healing in isolation. We need other people. Stan Tatkin, clinical psychologist, author, speaker, and developer of A Psychobiological Approach to Couple Therapy (PACT) along with his wife, Tracey Boldemann-Tatkin, says that we are hurt in relationship and we heal in relationship. The presence of those close to us makes a difference even in the most dire circumstances. Just to mention one study among thousands, a hospital in Illinois recently demonstrated that coma patients recovered more quickly when they were able to hear the voices of their family members.

Like it or not, we’re all on this crazy and amazing human journey together.

We can never be completely safe, but we can move toward relative safety in life and in our relationships. We will never have our needs met perfectly, and we will never be (nor have) the perfect parent. Thankfully, that’s not required for deep and lasting healing. As we grow out of our wounded self and become a more securely attached, resilient being, we can foster the same process in others, becoming intimacy initiators and connection coaches for our families, friends, and the larger world.

Let’s take a look at both sides of our parents’ behavior. Each of us is a work in progress, and I’m sure your parents had some unfinished business along with their more admirable qualities. You may find this exercise helpful in taking a deeper look into what was problematic and painful as well as the gifts your family bestowed. So often our memories of difficult times overshadow the benefits we may have gained, so this exercise is aimed at helping us see more of the whole picture—to acknowledge and grieve wounds as well as celebrate wisdom gained. Of course, often we gain wisdom and compassion from healing our wounds as well.

EXERCISE: Perfectly Imperfect

Part One—What Was Missing or Hurtful?

You may want to start this exercise by making a list of the shortcomings or failings of each of your parents—those circumstances or behaviors that had the most negative influence on you as a child. What happened is significant, and how you internalized it is even more so. Sometimes it’s easier to recount our parents’ negative attributes than it is to remember any of their positive ones, especially for those of us with an ambivalent or disorganized attachment style. Our negative experiences may overshadow the everyday neutral or basically good experiences we may have had until we regain a sense of them after healing many early wounds. People with the avoidant attachment style tend to see their histories as mostly fine, until feelings of longing resurface and they realize what they missed relationally.

Part Two—What Was Beneficial or Supportive?

My mother was a tough teacher. She lived with unresolved emotional distress, but she was also fun-loving and generous. Despite sometimes being a less-than-ideal parent, she had her own ways of expressing her love to me with special celebrations, generous gift-giving, helping me with projects close to my heart, and shopping for fun bargains we called “treasure hunting.” My father was similarly complex: he was out of touch with his emotional self and gone a lot for his work, yet he was able to convey his love quietly in a steadfast way through providing for the family, locking the doors at night, fixing my bike, teaching me to water ski, and grilling great food for picnics. He also had the core value of volunteerism that survives in our family to this day. Both of my parents did the best they could under the circumstances, and together they taught us important core values.

Try looking at each of your parents through the lens of how they may have shown you their love. Write down all the ways you have learned important lessons, skills, and insights from your most important caregivers. It can help to describe your mother and father on their best days. As best you can, give them the benefit of the doubt and consider that they were doing the very best they could with whatever level of unresolved trauma or attachment injury they lived with, as well as with whatever resources, education, and healing strategies they had available to them at that time. See if you can detect their deep care amid their imperfections and harming behaviors, no matter how murky or inarticulate they were in expressing that love for you. What do you find?

This is an excerpt from The Power of Attachment: How to Create Deep and Lasting Intimate Relationships by Diane Poole Heller, PhD.

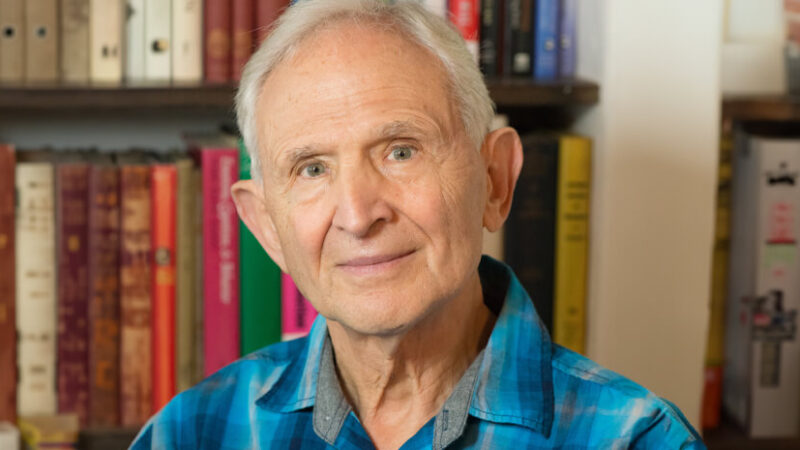

Diane Poole Heller, Ph.D., is an established expert in the field of Child and Adult Attachment Theory and Models, trauma resolution, and integrative healing techniques. Diane developed her own signature series on Adult Attachment called DARe (Dynamic Attachment Re-patterning experience) also known as SATe (Somatic Attachment Training experience). Dr. Heller began her work with Dr. Peter Levine, founder of SETI (Somatic Experiencing® Trauma Institute) in 1989. As Senior Faculty for SETI, she taught Somatic Experiencing® trauma work internationally for over 25 years. As a dynamic speaker and teacher, Diane has been featured at prestigious international events and conferences. She is the author of numerous articles in the field.

Diane Poole Heller, Ph.D., is an established expert in the field of Child and Adult Attachment Theory and Models, trauma resolution, and integrative healing techniques. Diane developed her own signature series on Adult Attachment called DARe (Dynamic Attachment Re-patterning experience) also known as SATe (Somatic Attachment Training experience). Dr. Heller began her work with Dr. Peter Levine, founder of SETI (Somatic Experiencing® Trauma Institute) in 1989. As Senior Faculty for SETI, she taught Somatic Experiencing® trauma work internationally for over 25 years. As a dynamic speaker and teacher, Diane has been featured at prestigious international events and conferences. She is the author of numerous articles in the field.

Her book Crash Course, on auto accident trauma resolution, is used worldwide as a resource for healing a variety of overwhelming life events. Her film, Surviving Columbine, produced with Cherokee Studios, aired on CNN and supported community healing in the aftermath of the school shootings. Sounds True recently published Dr. Heller’s audiobook Healing Your Attachment Wounds: How to Create Deep and Lasting Relationships, and her book, The Power of Attachment: How to Create Deep and Lasting Intimate Relationships.

As a developer of DARe and president of Trauma Solutions, a psychotherapy training organization, Dr. Heller supports the helping community through an array of specialized topics. She maintains a limited private practice in Louisville, Colorado.

Buy your copy of The Power of Attachment at your favorite bookseller!

Sounds True | Amazon | Barnes & Noble | Indiebound