Dear Sounds True Friends,

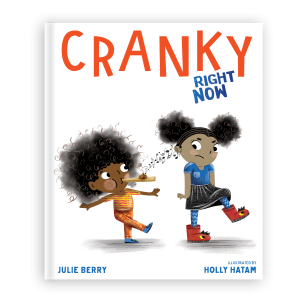

“Cranky” is a perfect word. It feels like it sounds; the way it forms in your mouth fits the emotion. It’s perfect for that place between truly sad and properly angry, for times when we ought not to get so upset about trifling things, but we can’t help it. At least, not at first.

We’re allowed to be sad when hard times come. We’re allowed to be angry in the face of real injustice. But the papercuts of life? The whacked elbows and burnt toast, the stolen parking spots and somebody-took-the-last-cookie days? Not so much.

We’re supposed to take those moments in stride. We’re supposed to maintain our equilibrium. But moods are unruly and feelings don’t like to be bossed around. “Cranky” is the perfect word for those times when we feel resentful, irritated, and annoyed, but we know our cause isn’t especially sympathetic. When Murphy’s Law strikes, and we’re not yet ready to laugh it off.

I’m supposed to be patient and mature at times like these, but I can be a great big Crankypants. Knowing I’m not supposed to feel cranky only makes me more cranky. Next thing you know, I’m spiraling. (I’m probably the only one …)

Kids are no different. Life in families presents us all with nuisances and irritations. No one escapes a school day or a trip to the store unscathed. Life jostles us, but for kids, whose time and choices are largely directed by others, those feelings of powerlessness, of being managed and judged by someone who just doesn’t get it—and to be fair, sometimes we don’t get it; we weren’t there; we are quick to assume—those feelings can be maddening.

I wrote Cranky Right Now to give kids, parents, families, and teachers a way to talk about cranky times. and especially, a way to laugh about them. Illustrator extraordinaire Holly Hatam’s hilarious illustrations bring the magic. I hope you’ll giggle along with the vexed heroine of Cranky. It’s actually the first step forward. It’s easier to spot the absurdity in someone else’s cranky fit than our own, but the lessons still sink in. Humor is a powerful antidote to being a Crankypants.

Sometimes simply having that perfect word, “cranky,” in our arsenal helps. When we can recognize, “Hey, I’m not actually deeply upset right now; everything’s more or less okay; I’m just cranky right now, and it will pass,” we’re already halfway home.

So get ready to giggle at the heroine of Cranky Right Now as she explores strategies for coping with crankiness. They may help the young people in your life. They may even help you. Not that you have a crankiness problem! Heavens, no. It’s those others around you. They started it …

Yours in absurdity,

Julie Berry

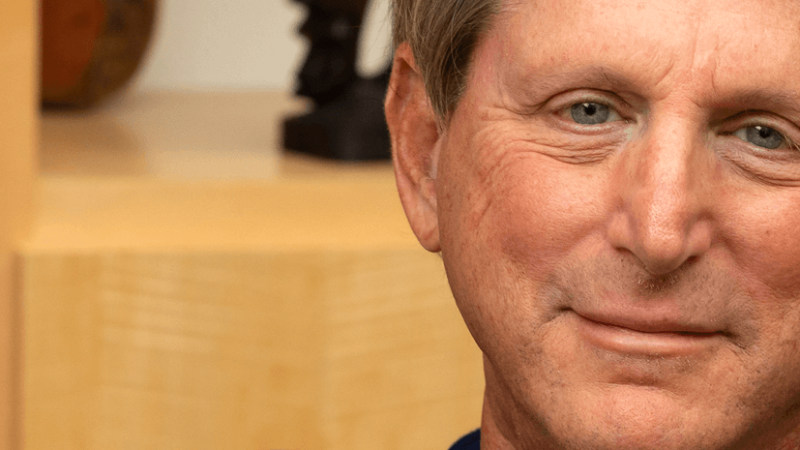

JULIE BERRY is the author of many books for children, including Wishes and Wellingtons, The Scandalous Sisterhood of Prickwillow Place, and Happy Right Now. Her novel Lovely War was a New York Times bestseller, and The Passion of Dolssa was a Printz Honor title. Three things that make Julie cranky are paperwork, chewed pens and pencils, and mornings that come too soon. She lives with her family in Southern California. Learn more at julieberrybooks.com.

JULIE BERRY is the author of many books for children, including Wishes and Wellingtons, The Scandalous Sisterhood of Prickwillow Place, and Happy Right Now. Her novel Lovely War was a New York Times bestseller, and The Passion of Dolssa was a Printz Honor title. Three things that make Julie cranky are paperwork, chewed pens and pencils, and mornings that come too soon. She lives with her family in Southern California. Learn more at julieberrybooks.com.

Learn more and buy now

Amazon | Barnes & Noble | IndieBound | Bookshop | Sounds True