-

E117: The Real Work: Letting Go from Within

Michael Singer — October 2, 2025

True spirituality isn’t about mystical experiences or lofty ideals—it’s about honestly facing...

-

Once More: Reflections on Reincarnation and the Gap Between Lives

Tami Simon — September 26, 2025

In this special reflection episode of Insights at the Edge host Tami Simon looks back on her...

-

Honey Tasting Meditation: Build Your Relationship with Sweetness

There is a saying that goes “hurt people hurt people.” I believe this to be true. We have been...

Written by:

Amy Burtaine, Michelle Cassandra Johnson

-

Many Voices, One Journey

The Sounds True Blog

Insights, reflections, and practices from Sounds True teachers, authors, staff, and more. Have a look—to find some inspiration and wisdom for uplifting your day.

Standing Together, and Stepping Up

Written By:

Tami Simon -

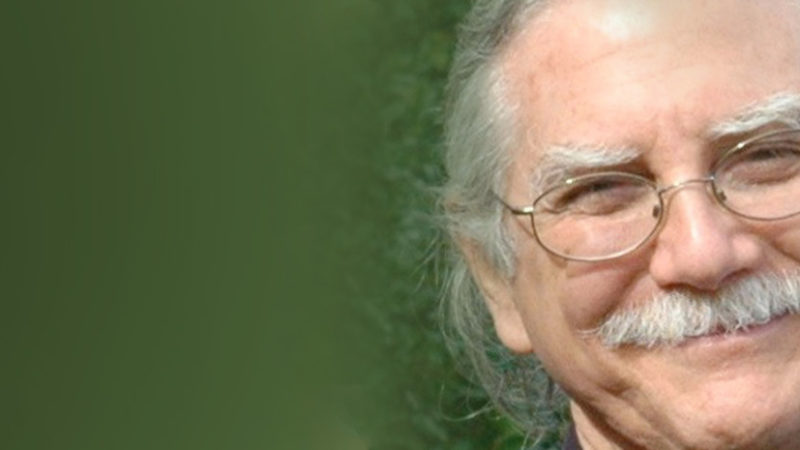

The Michael Singer Podcast

Your Highest Intention: Self-Realization

Michael Singer discusses intention—"perhaps the deepest thing we can talk about"—and the path to self-realization.

This Week:

E116: Doing the Best You Can: The Path to Liberation -

Many Voices, One Journey

The Sounds True Blog

Insights, reflections, and practices from Sounds True teachers, authors, staff, and more. Have a look—to find some inspiration and wisdom for uplifting your day.

Take Your Inner Child on Playdates

Written By:

Megan Sherer

600 Podcasts and Counting...

Subscribe to Insights at the Edge to hear all of Tami's interviews (transcripts available, too!), featuring Eckhart Tolle, Caroline Myss, Tara Brach, Jack Kornfield, Adyashanti, and many more.

Most Recent

How to Stop Turning Your Back on Your Trauma

We Suffer Ahead of Time

There is a kind of pain that is born from the anticipation of something that we know will happen but has not yet happened. We suffer a lot for things that have not yet happened. We anticipate, in excruciating detail, the pain of a visit to the dentist or a planned surgery. We spend several months suffering the pain of giving birth. We suffer for the death of a loved one months before cancer takes their life. We suffer for things that do not yet hurt, in such a way that when real pain does arrive, our body and mind are already exhausted.

Our bodies are wise; this we have said already. Our bodies and our minds feel the impulse to repair the damage detected. When we feel pain, we activate a repair system with the objective of recovering the balance lost. But we must take care not to end up like Peter in the tale of “Peter and the Wolf”: he warned so many times about the wolf coming, without it being true, that when it did truly arrive, nobody believed him. If we activate the alert mechanism in the face of pain ahead of the time, then, when we need them the most, we won’t have any resources left to cope with it.

The source of emotional pain is often caused by:

- Adversity

- Frustration

- Disappointment

- Unexpected change

- Judgments and thoughts

- Reality

- Imagination

- Fear

- Anticipation

Suffering and adversity are just part and parcel of life. Any day we might experience the greatest and most unexpected of tragedies. But what really matters is not what could or might happen to us—which can be just about anything—but what is actually happening to us. When we speak about misfortune and adversity, we must speak about probabilities, not possibilities, namely the likelihood that any of the adversities we are exposed to might occur. Is there a chance that a piece of space debris might fall from outer space and split my head open? I don’t have the evidence to deny it. However, if I am going to be afraid of anything, in my case it would be the cows I meet in the mountains when I’m out for a run because it’s far more likely that I will be trampled by a cow than get hit by a piece of space debris.

So, if you ever ask yourself, “Why me?” remember that we are fragile; that we live in a hostile environment; and that sometimes, with the behaviors and the decisions that we make—or don’t make—we are taking risks that can lead us to adversity. However, at other times, the cruelest fate hits us with adversity.

Building a Wall Is Not the Solution

Some people think that the solution to live more at ease is to build a wall to defend themselves. Do not make that mistake; the wall will defend you from exterior aggressions, but it will also prevent you from enjoying the wonderful things around you. If you build a wall, you will prevent disappointment, but you will feel bitterly lonely. A wall can protect you from fear of change but will create an inability to adapt to different situations. The wall will provide you with safety, but it will also make you a person who is dependent on its protection; it will make you insecure and fearful of what will happen when that wall disappears. I encourage you to build, instead of a wall, a library full of resources to help you maintain the level of emotional strength that you need.

What’s more, when we attempt to protect ourselves by adopting strategies that are damaging, and when we wear armor, we disconnect emotionally from the people around us and from reality. Building a wall is never the solution because it will not protect us from that pesky space debris looming above our heads. Don’t forget: prudence is good, fear is not.

Reflection Exercise

I encourage you to do an exercise. Analyze the pain you are experiencing and try to identify its source. Don’t leave it for tomorrow. Don’t click to the next site just yet. Just pick up a notebook and a pencil, find a quiet place right now, and reflect. Take action, because it’s up to you to do something about this. Nobody will do it for you.

Learn more about this powerful practice of healing trauma in Kintsugi: The Japanese Art of Embracing the Imperfect and Loving Your Flaws by Tomás Navarro.

Tomás Navarro is a psychologist who loves people and what they feel, think, and do. He is the founder of a consultancy practice and center for emotional well-being. He currently splits his time between technical writing, training, consultancy, conferences and advisory processes, and personal and professional coaching. He lives in Gerona and Barcelona, Spain.

Theresa Reed: Monkey Mind

They say that animals often come to resemble their owners. Or maybe it’s the other way around. I am not sure where that statement came from, but I would probably say there is a nugget of truth to it. Perhaps we do become more like our critters, or more likely, we simply learn from them.

A decade ago, my husband and I adopted a little black cat from the local shelter. As soon as they plopped him in our hands, he began to purr like a motor. We bundled him up, took him home, and named him Monkey.

This name seemed to fit him much better than his original moniker, Phantom. Monkey wasn’t a cat who liked to hide away, and he wasn’t very stealthy either. Instead, he was restless, animated, and liked to play rough. Always in movement, he could barely sit still long enough for a picture. He’s got a true “monkey mind.”

I hate to admit this, but in a way we’re a lot alike.

Like Monkey, I am easily distracted. I blame this on my Gemini ways, but the truth is that’s not an excuse for having too many projects running at the same time with all the technology in the world clamoring for my attention. The blips and dings that alert me that I’ve got mail or texts or other such things keep me in a state of high alert. “What’s happening? What’s going on?” Or, more accurately, “What did I miss?”

Like a pinball whizzing around the flippers and bumpers, my brain is in constant motion. Sometimes I’ve found myself amazed that I was able to get anything done at all.

My writing sessions were punctuated by petting sessions, and cooking a meal required one hand on the spatula while another held a laser pointer to keep Monkey from biting my heels. Disruption via feline was a way of life around my house, so, as you can imagine, it wasn’t easy for a focus-challenged person like myself to remain present much of the time.

One day, I was tapping away on the computer when I noticed Monkey staring down a bug. He was poised to pounce, eyes wide, and completely still. The bug wasn’t moving. Neither was Monkey. This was a total showdown between cat and bug—and neither was going to move until the time was right.

Fascinated, I stopped what I was doing to watch this duel unfold.

The stare-down continued for a few minutes. This cat wasn’t going to flinch until he witnessed a glimmer of activity. Finally, I saw a flicker of movement as the bug slowly lifted his leg. Monkey’s eyes widened as he wriggled his bottom. Suddenly he pounced on the hapless bug, and in an instant, it was over. The bug was lying face up, with no sign of life. Monkey sniffed around it for a second, then sauntered away. The job was done and now it was time for a nap in the sun.

I found myself pondering this long after the deed was over.

How could this cat, who detests the house rules and who seems to be in constant squirm motion, remain so deeply engrossed? How is it that Monkey was able to deftly finish his work while I sat at my desk, still stuck on finding the first opening sentence for my latest project?

The truth was staring me in the face as the little familiar beep that alerted me to an incoming text pulled me away from my work.

I had created a maelstrom of technology and distraction around me. This was preventing me from effectively “killing the bug.” If I was going to be prolific, effective, and calm in both my work and my spiritual practice, I needed to set myself up for success. It was time to commit to making my world distraction-free so I could tame my own monkey mind.

This is an excerpt from a story written by Theresa Reed and featured in The Karma of Cats: Spiritual Wisdom from Our Feline Friends, a compilation of original stories by Kelly McGonigal, Alice Walker, Andrew Harvey, and many more!

Theresa Reed has been a professional, full-time tarot reader for more than 25 years. A recognized expert in the field, she has been a keynote presenter at the Readers Studio, the world’s biggest tarot conference, and coaches tarot entrepreneurs via numerous online courses and her popular podcast, Talking Shop. Theresa lives in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. For more, see thetarotlady.com.

Michael Singer: Living From a Place of Surrender

Michael Singer is a spiritual teacher, entrepreneur, and the bestselling author of the spiritual classic The Untethered Soul. He has collaborated with Sounds True to release the online course Living from a Place of Surrender: The Untethered Soul in Action. In this episode of Insights at the Edge, Tami Simon speaks with Michael about the core idea of his teachings: that it is only through complete surrender to the essence of the moment that we experience life’s full potential. They talk about what this sense of surrender actually means when it comes to decision-making and day-to-day activities, as well as how to recognize when we are still clinging to resistance. Michael explains how to take a “witness position” and let go of the arbitrary attachments that inhibit surrender. Finally, Tami and Michael discuss the application of these ideas to those things we truly value, including bringing the idea of surrender to social and environmental activism. (63 minutes)

Customer Favorites

Joseph Marshall III: Wisdom of a Lakota Elder

Joseph M. Marshall III is a teacher, historian, writer, storyteller, and a Lakota craftsman. Joseph’s expansive body of work includes nine nonfiction books, three novels, and numerous essays, stories, and screenplays. With Sounds True, he has produced the audio programs Quiet Thunder and Keep Going, as well as the book The Lakota Way of Strength and Courage. In this episode, Tami talks with Joseph about the inheritance of wisdom he received from his grandparents, the central teachings of the Lakota people, the sense of guilt and shame that many Euro-Americans feel when reflecting on the tragedies of American history, and a story about the power of awareness and looking back. (48 minutes)

Goldie Hawn: Moving in a Direction That Matters

Goldie Hawn is an Academy Award-winning actor, director, producer, and activist best known for her roles in films such as Cactus Flower, Private Benjamin, and Death Becomes Her. She created The Hawn Foundation, the nonprofit organization behind MindUP™, an educational program that is bringing mindfulness practices to millions of children across the world. In this episode of Insights at the Edge, Tami Simon speaks with Goldie about her longtime interest in meditation and why it’s so important to teach brain basics to kids. They discuss the neuroscience that demonstrates the clear benefits of teaching emotional intelligence, mindfulness, and the basics of brain science to children from an early age—as well as why Goldie is teaching these aspects to her own grandchildren. Finally, Tami and Goldie talk about what it means to differentiate one’s true self from the projections of others, as well as why love and family remain Goldie’s first priorities in life. (67 minutes)

Anna Goldfarb: Wholehearted Friendship

Friendships aren’t always easy and fun. Like all meaningful relationships, they require work. They require nurturing and a willingness to grow. And in today’s world, explains author and journalist Anna Goldfarb, many friendships are being pushed to the brink and painfully ending. In this podcast, Tami Simon speaks with Anna about her new book, Modern Friendship, an empowering guide to creating what she calls “wholehearted friendships.”

Enjoy this conversation that’s filled with insights and strategies you’ll find especially helpful in our isolated, hyper-fluid society. Tami and Anna discuss: the increasing ambiguity of 21st-century friendships; the false promise of social media; the core elements of a successful friendship strategy; memorial friendships vs. active friendships; Jacuzzi friends, bathtub friends, and pool friends; three main causes of friendship breakups; the three requirements—consistency, positivity, and vulnerability; choosing people with whom you can share meaning; the characteristics of wholehearted friendship; and more.